Kotlin Collections

The Kotlin collections are actually direct instances of the collections in the JDK. There’s no conversion of wrapping involved. So, if you didn’t skimp on your study of collections while you were in Java, that will certainly come in handy now. Although Kotlin didn’t define its own collections code, it did add quite a few convenience functions to the framework, which is a welcome addition because it makes the collections easier to work with.

Before we go to the code examples and more details, something needs to be said why it is called a collections framework. The reason it’s called a framework is because the data structures are very diverse, in and of themselves. Some of them puts constraints on how we go through the collection, they impose certain order of traversal. Some of the collections constrains the uniqueness of the data elements, they won’t allow you to put duplicates. And some of them lets us work with the collections in pairs, like in a dictionary entry, you’ll have a key with a corresponding value.

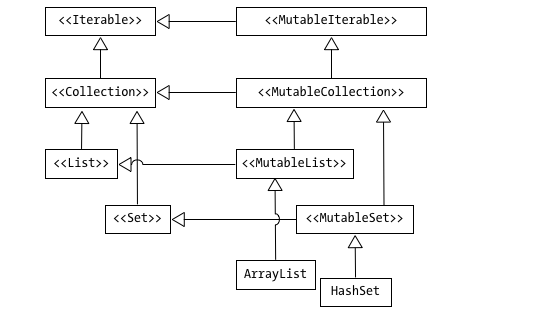

.At the top of the hierarchy are the interfaces Iterable and MutableIterable — refer to the big image at the beginning of this article. They are the parents of all the collection classes we will work with. As you may have noticed in the diagram, each Java collection has two representations in Kotlin; a read-only one and a mutable one. The mutable interfaces map directly to the Java interfaces while the immutable interfaces lack all of the mutator methods of their mutable counterparts.

Kotlin doesn’t have a dedicated syntax for creating lists or sets, but it does provide us with library functions to facilitate creation. Table 1 lists some of them.

Table 1. creation functions for collections

| Collection | read only | read-write |

|---|---|---|

| list | listOf |

mutableListOf, arrayListOf |

| set | setOf |

mutableSetOf, hashSetOf, linkedSetOf, sortedSetOf |

| map | mapOf |

mutableMapOf, hashMapOf, linkedMapOf, sortedMapOf |

List

A list is a type of collection that has a specific iteration order. It means that if we added a couple of elements to the list, and then we step through it, the elements would come out in a very specific order — it’s the order by which they were added or inserted. They won’t come out in a random order or reverse chronology, but precisely in the sequence they were added. It implies that each element in the list has a placement order, an index number that indicates its ordinal position. The first element to be added will have its index at 0, the second will be 1, the third will be 2, so on and so forth. So, just like an array, it is zero-based

Set

Sets are very similar to lists, both in operation and in structure, so, all of the things we’ve learned about lists applies to sets as well. Sets differ from lists in the way it puts constraints on the uniqueness of elements. It doesn’t allow duplicate elements or the same elements within a set. It may seem obvious to many what the “same” means, but Kotlin, like Java has a specific meaning for “sameness”. When we say that two objects are the same, it means that we’ve subjected the objects to a test for structural equality. Both Java and Kotlin defines a method called equals() which allows us to determine equivalence relationships between objects. This is generally what we mean by “sameness”.

Map

Unlike lists or sets, maps aren’t a collection of individual values, but rather, they are a collection of pairs of values. Think of a map like a dictionary or a phone book, its contents are organized using a key-value pair. For each key in a map, there is one and only one corresponding value. In a dictionary example, the key would be the term, and its value would be the meaning or the definition of the term.

The keys in a map is unique. Like sets, maps do not allow duplicate keys. However, the values in a map are not subjected to the same uniqueness constraints , two or more pairs in map may have the same value

Collection Protocols

The Kotlin team probably didn’t refer to the set of actions you can do on collections as “collections protocol”, I just thought it would be cool to borrow the term from Python . Anyhoo, one of the benefits of working with the collections framework is that, your knowledge and skill on lists, for example, commutes nicely to sets and maps. This way, you learn a set of skills for one kind of collection and you can use it on the other two. This is one of the reasons it’s called a framework.

Table 2. Common things you can find or do in the collection classes

| function or property | description |

|---|---|

size |

tells you how many elements are in the collection. Works with lists, sets and maps |

isEmpty() |

returns True if the collection is empty, False if it’s not. Works with lists, sets and maps |

contains(arg) |

returns True if arg is within the collection. Works with lists, sets and maps |

add(arg) |

add arg to the collection. This function returns true if arg was added — in the case of a list, arg will always be added. In the case of a set, arg will be added and return true the first time, but if the same arg is added the second time, it will return False. This member function is not found on maps |

remove(arg) |

returns True if arg was removed from the collection, returns False is the collection is unmodified |

iterator() |

returns an iterator over the elements of the object. This was inherited from the Iterable interface. Works with lists, sets and maps |

Traversing collections

The Collections class inherits from the Iterable interface. That means all Collections classes is also an Iterable object. What that means is, we can get an iterator object from a Collections class. An iterator lets us step through the elements of an object. In each step, the value of the element is exposed to us, we can use in whatever way we want e.g. assign it to a variable, transform it or store it somewhere else, etc.

Sample code below shows how to create an immutable list of Strings and walk through each of its elements. You’ve probably done quite a lot of these when you wer coding in Java

val basket = listOf("apple", "banana", "orange")

var iter = basket.iterator()

while (iter.hasNext()) {

println(iter.next())

}

for (i in basket) {

println(i)

}

The sample code below is another way of traversing the same list of Strings, but this example uses the forEach function. This is a lot shorter, and is the preferred way, some people would even say, idiomatic way, of working with Kotlin collections.

fruits.forEach { println(it) }